Arctic Landscapes

Why are the Arctic river deltas important to understand?

Arctic river deltas are crucial links between the vast Arctic land and the Arctic Ocean, transporting sediments, nutrients, and organic carbon. Their source regions, namely the Arctic and the sub-Arctic, contain a huge amount of soil-organic carbon locked within the permafrost. As the climate warms and permafrost thaws, the carbon will be liberated and potentially exacerbate the warming through positive feedback. On the other side of the deltas, the Arctic Ocean is also becoming increasingly free of ice, which is an important participant in shaping and maintaining the structure of Arctic deltas. Since the Arctic warms a few times faster than the global average (the so-called “Arctic amplification”), understanding these river deltas that serves as records and filters of carbon-containing matters becomes ever more important. Implications include whether the transported organic carbon would be trapped on the delta, be consumed and cycled by organisms and released into the atmosphere, or quickly discharged into the ocean and eventually buried there.

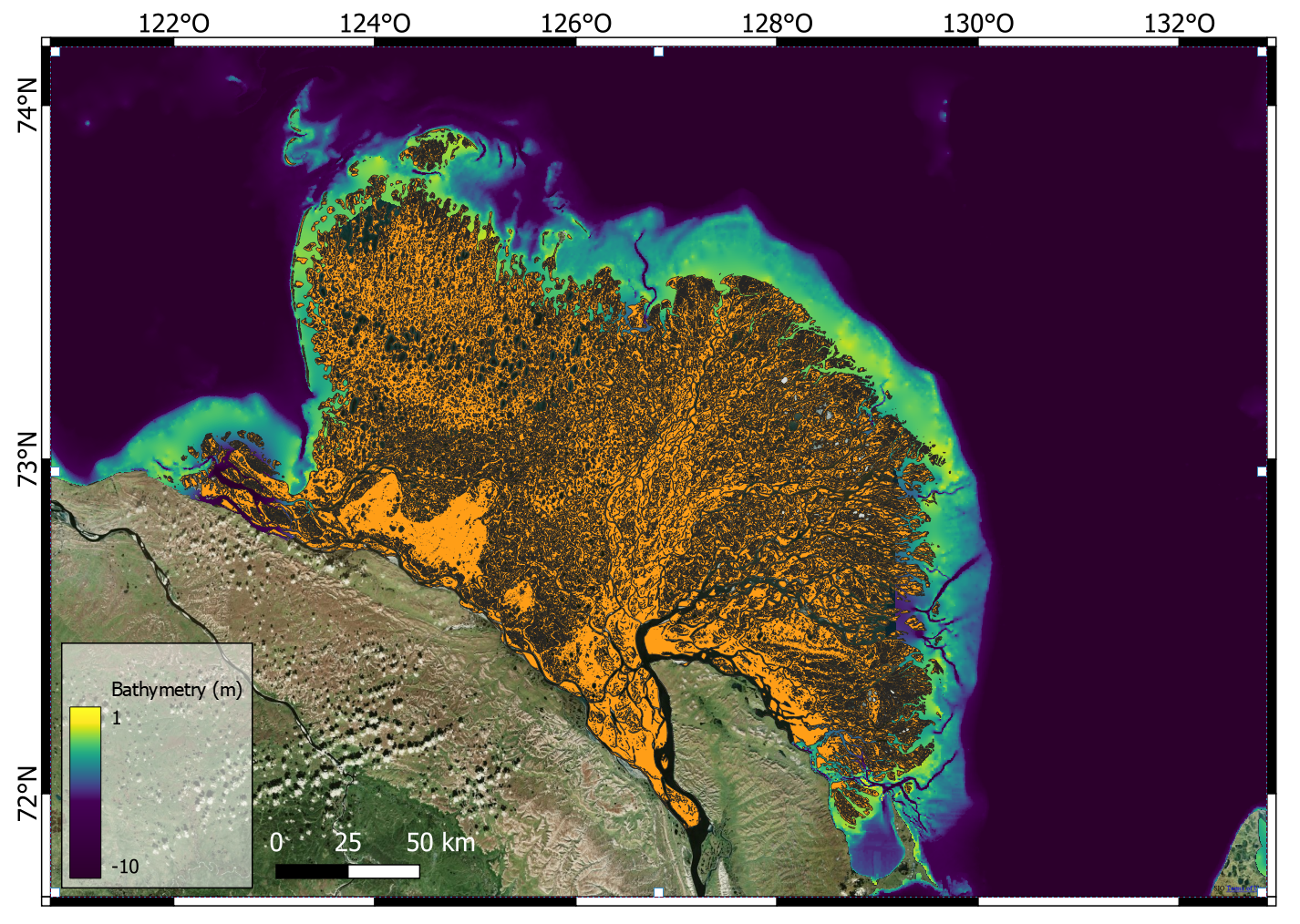

Unique are the “ramps” that appear to be ubiquitous to Arctic deltas. These ramps are gradual underwater inclines extending from the shoreline into the shallow waters, and effectively surrounds the entire delta. Due to their morphorlogy, these ramps may help mitigate coastal erosion. They could also serve as a sink to carbon-carrying sediments. Climate change threatens these deltas by thawing permafrost and altering ice conditions, which could drastically impact local ecosystems and global carbon cycles. Understanding these changes is therefore of great importance.

Map view of the Lena River Delta in Siberia. The orange part shows the delta itself. The colours in the below-water area shows the bathymetry. The ramp feature is clearly visible in the yellow to green-blue areas. Figure courtesy of Bennett Juhls, one of the co-authors of this study.

What is challenging and different about Arctic deltas?

River deltas are complex systems. They form as a result of a complicated interplay between the source river, the characteristics of the sediments they carry, and the currents (including tidal) in the ocean. For example, the speed, width, depth, and course of the river and its channels on the delta could influence the capacity to carry, pick up, or deposit sediments. These sedimentary particles’ size and mass form an intricate interplay with the water flow. Moreover, as sediments get picked up (i.e., eroded) or deposited, the river and streams would branch into smaller channels and/or change course, forming the constantly evolving structure and shape of the deltas. Detailed simulation of a delta beyond the time span of days is still unfeasible, let alone simulating the centuries and millenia needed for deltas to form and evolve. Arctic deltas present additional challenges: permafrost and ice. Permafrost is hard and resists mechanical erosion, but is suceptible to thermal erosion, which behaves quite differently. Moreover, the freeze-thaw cycle of ice between seasons also affects the erosional/depositional characteristics of the river channels. Due to the south-to-north flow direction of most Arctic rivers, ice also melts from source towards the river mouth, causing short but extremely violent ice jams and flooding close to and on the deltas. On the ocean side, sea ice also influence water and sediment flow between seasons. The only way to simulate long-term evolution of Arctic deltas is therefore through a set of complex and self-consistent rules to make all the highly non-linear physics tractable. The resulting class of models is referred to as “reduced complexity models” (RCMs).

What did we do and find?

Our study built upon earlier works to create an RCM that is able to reproduce a ubiquitous “ramp” feature seen in Arctic deltas but not in earlier computer models. We also found that the size of the ramps are influenced by the following factors: (i) the thickness and extent of winter ice, (ii) the available depth in the ocean basin under the winter ice cover, and (iii) the timing of the melting of grounded ice (i.e., ice that is anchored to the ground below and not floating) from atmospheric heat. By examining data taken from the Lena River Delta in Eastern Siberia, we found that gounded ice resting on top of the ramp also has a protective effect during the annual flood (due to ice jams and the large amount of melt water from the south), preserving the ramp from being eroded away.

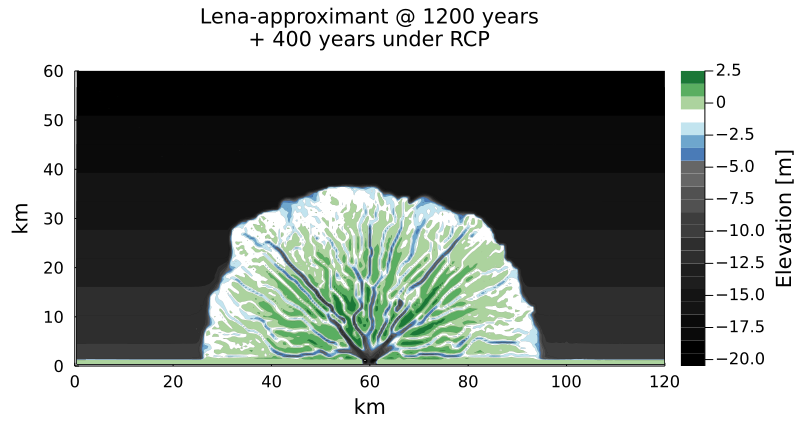

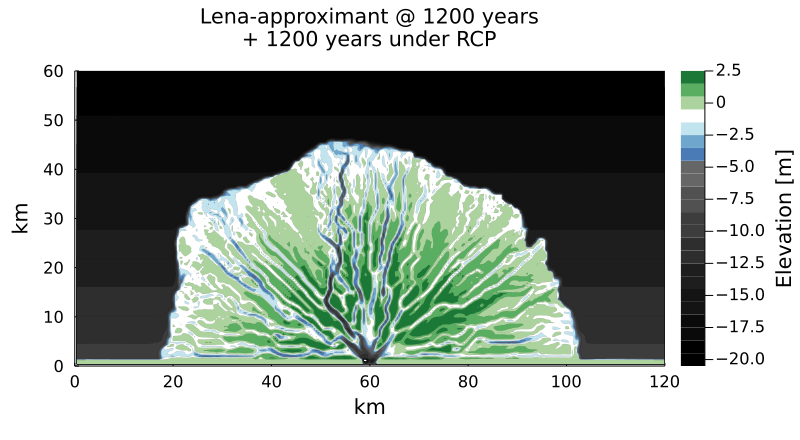

We also ran some large simulations of a delta with size and characteristics comparable to the Lena Delta (see the figures below). We first formed the stable ramp feature over 1200 years. Then, we continue the simulation into the future, but under a climate-change scenario. We found that its ramp feature, which has so far been stable, will degrade in a matter of centuries and effectively vanish in a millenium.

A delta simulated with size, conditions, and characteristics comparable to the Lena Delta in Siberia. The colours show elevations relative to the sea surface. The top panel shows the simulated delta after 1200 years under existing climate and river-flow conditions. The ramp is visible in the white to blue-tinted contour colours. The second panel shows the further evolution of the delta after 400 years, but with climate and flow conditions expected in a strong climate-warming scenario. Note the degradation of the ramp (i.e., less white and blue buffer areas on the shoreline). The bottom panel shows the same simulation at 1200 years into the future. The ramp is practically gone.

Click here to read our published arcticle. 😉

The article on this page, all related graphics and picture (unless otherwise specified) © Ngai Ham Chan.

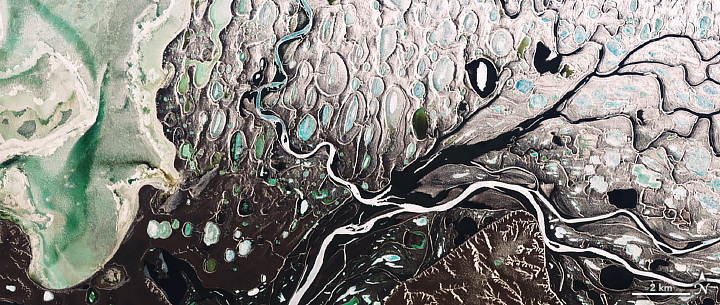

End of page image: NASA Earth Observatory image by Joshua Stevens.